Rights of way – alley spat in Harrogate

The problems can be particularly acute during the construction works, when contractors might quite literally cut corners when using access roads, cause disruption when stopping to unload materials or park in such a way as to make it difficult for others to pass.

This can be infuriating for the road-owner and others allowed to use it. That does not, however, mean that they can necessarily do anything about it.

This was the situation the Court was faced with in AJP Homes Ltd v Tate Estates (Lambert House) Ltd & Another [2024].

The road-owner’s claim was unsuccessful in this case, but the decision serves as a reminder that each case is different and will turn on a careful reading of the rights that have been granted. It also contains an interesting discussion about when a landowner might, and might not, be found to be liable for the actions of their chosen building contractors.

The problem

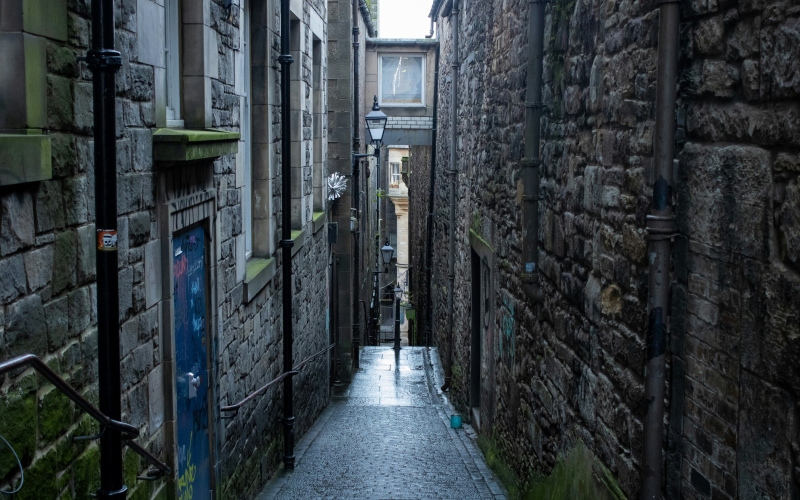

The case concerned a property in Harrogate.

Originally, the property was owned by one person. The site comprised residential houses at the front with a commercial unit at the rear. The two areas were separated by a small alley at the back and shared an access road to the side.

In 2016, the owner obtained planning permission to demolish the commercial unit at the rear and build six residential properties in its place. The owner sold the commercial unit to a developer later on in 2016. The developer went on to obtain its own planning consent to construct 12 (rather than six) residential apartments with undercroft parking.

The 2016 transfer by which the commercial unit was sold-off contained various rights in favour of the developer and future owners. These included a right of way to use the access road and the alleyway at the back, and a right to park in a designated area.

The land at the rear was subsequently sold-on to Tate in 2018. The houses at the front where subsequently sold to AJP in 2021. Unfortunately, tensions between AJP and Tate grew during the construction of the 12 new apartments.

AJP issued proceedings against Tate, and against Tate’s building contractor, seeking compensation for having acted outside the terms of the 2016 transfer. It said that the access road and alleyway were being used in ways that were not permitted by the transfer, including by stopping for the purposes of loading and unloading.

AJP argued, further, that the right of way did not allow Tate or any of the new residential owners to use the access road and alley as a means to get to the entrance of the new undercroft parking area, and claimed that Tate was liable for numerous acts of trespass committed by its contractors during the building works.

Tate counterclaimed alleging that AJP had wrongfully interfered with the rights of way that it had been given. AJP had erected a temporary metal fence on part of the access road that Tate said had impeded deliveries, forcing materials to be carried to site by hand resulting in delays to completion.

The building contractor went into administration in 2022 and effectively dropped out of the picture.

Did the right of way include a right to stop to load and unload?

The 2016 transfer gave the owner of the land to the rear an express right to pass with or without vehicles over the accessway for all purposes connected with the property.

The Court had to determine whether the right to pass over the accessway allowed Tate and those authorised by it to stop on the road, including to load or unload materials.

The scope and extent of a right of way that has been granted by a transfer depends on the interpretation of the wording used.

The Court will construe the language of the transfer in light of the circumstances and the intention of the parties at the time the rights were granted. Determining the extent of the rights is therefore a matter of contractual interpretation.

The Judge ultimately found that the right of way did include a right to stop and load/unload as long as this did not cause a blockage.

A reasonable person having the background knowledge available to the original parties in 2016 (including the 2016 planning permission) would have understood that there was such a right, in light of: (i) the natural and ordinary meaning of the words used; (ii) additional provisions in the transfer that only made sense if there was a right to stop; (iii) the overall purpose of the clause; (iv) the facts and circumstances known by the parties at the time the rights were granted; and (v) commercial common sense.

Could the accessway be used to get to the entrance to the parking area?

Contractual interpretation is not just about finding the ordinary or natural meaning of words in a document. The Court has to find the meaning that the document would convey to a reasonable person having the background facts known or available to the parties.

This means that the words used in a document, whilst important, are not necessarily determinative.

AJP tried to argue that the wording of the right of way – to pass for all purposes connected to the property at the rear – were only part of the jigsaw. It argued that the background and physical features in 2016 showed that access to the rear property was envisaged to be by a different route. This, it said, meant that Tate and any new owners could only pass over the access road to get to the parking spaces as originally shown in the 2016 planning consent, and not to get to the entrance to the new undercroft parking area in the 2017 consent which was in a different location.

The Judge rejected that argument.

In the Judge’s view, although the words used were not determinative, the meaning of those words is most obviously gleaned from the language used. The clearer the natural meaning, the more difficult it is to justify departing from that meaning.

The 2016 transfer was also a professionally prepared agreement. If the parties had intended that the alley could only be used in the limited way that AJP contended, clear words could and would have been used.

The Judge found that the 2016 transfer did not require the rear land to be built only in accordance with the 2016 planning consent or, therefore, restrict where the entrance might be.

The Judge concluded that a reasonable person would understand that a “right of way for all purposes” had a wide meaning. They permitted Tate and any new owners to use the alley for other purposes connected with the rear property, including to gain access to the undercroft parking area via the new entrance and to stop for the short time it would take for the shutter to the car park to open.

Was Tate liable for acts of trespass committed by its contractor?

AJP alleged that the building contractor had exceeded the terms of the right of way (for example, by storing materials and parking where they were not allowed), and, by doing so, had committed a trespass.

AJP took this argument further, however. It claimed that Tate was jointly responsible for the acts of trespass committed by its building contractor.

There are circumstances in which someone can be held responsible for the acts of a third party. This is often the case in an employment situation, where an employer is vicariously liable for acts carried out by an employee in the course of their employment. This can also arise in relationships “akin to employment”, such as partnerships.

However, the general rule is that someone that engages an independent contractor is not liable for the acts committed by the contractor in the course of the execution of the work.

However, a person that engages an independent contractor may still be liable themselves in some circumstances. For example, if that person has negligently selected an incompetent contractor, or interferes with the way in which the independent contractor carries out the work to such an extent that they cause damage. They may also be liable if they authorise or ratify the independent contractor’s wrongful actions.

In this case, the Judge found that there was no suggestion, or evidence, that Tate had selected an incompetent contractor, interfered with the manner in which the contractor had carried out the works or done anything to ratify the contractor’s actions.

The Judge accordingly concluded that Tate was not liable for any of the acts of trespass by the building contractor.

The Judge found that most of the 31 alleged acts of trespass were not made out anyway. The rights of way permitted the contractor to do some of the acts complained of (such as stopping to unload materials), and in other instances the photographic and other evidence did not substantiate the allegations.

Even where claims of trespass were conceded or proved (such as the depositing of some materials on, and unlawful parking outside of, the right of way), the Judge considered them to have been insignificant and lasted only for a short time.

There were very few acts that the Judge thought that were significant. These included the placing of a site cabin and skip where they shouldn’t have been, and the storage of flooring and stone wall materials for days rather than hours. But even these would only have justified negotiating damages in the low thousands of pounds, for which the building contractor, and not Tate, would have been liable.

Did AJP interfere with Tate’s right of way?

In an attempt, so it said, to force the contractor to abide by the terms of the rights of way, and to comply with relevant health and safety obligations, AJP erected a temporary, movable, metal fence on part of the access road.

The Judge thought it much more likely, however, that the fencing had been erected in a “fit of pique”.

Although the Judge was satisfied that the fencing had wrongfully interfered with Tate’s right of way for some 10 months, they did not believe that the fencing was the cause of delays to the building schedule.

Even if the fencing had caused the delays, Tate’s counterclaim would likely have been for a nominal amount only (not the £300,000 claimed).

WolfBite

The types of issues raised in this case are typical of many of the disputes that we deal with involving rights of way and access roads.

This case helps to demonstrate that each such case will, however, ultimately turn on the specific wording of the rights that have been granted, and the surrounding facts. One case is never the same as another. A proper analysis is required, and similar sounding words and phrases can sometimes produce very different outcomes.

The judgment also demonstrates the difficulties in trying to hold a neighbour liable for the actions of the independent contractor they have engaged. It will usually be necessary to pursue the independent contractor directly for any acts of trespass. However, as AJP found out, independent contractors may not always be worth suing.

If you would like to find out more about rights of way or others issues arising out of property development, just send an email to hello@hagenwolf.co.uk or call us on 0330 320 1440.

LEEDS

One Park Row

Leeds,

West Yorkshire

LS1 5AB

Phone: +44 (0) 113 856 0446

Email: hello@hagenwolf.co.uk

Web: www.hagenwolf.co.uk

LONDON*

One Pancras Square

King's Cross

London

N1C 4AG

Phone: +44 (0) 207 846 4146

Email: hello@hagenwolf.co.uk

Web: www.hagenwolf.co.uk

NEWCASTLE*

Bank House

Pilgrim Street

Newcastle

NE1 6QF

Phone: + 44 (0)191 300 2756

Email: hello@hagenwolf.co.uk

Web: www.hagenwolf.co.uk

*‘We do not take service at our London and Newcastle offices. All meetings, at all of our offices, are by appointment only.

Hägen Wolf Limited (trading as Hägen Wolf) are solicitors of England and Wales authorised and regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority SRA Number 659328. Details of the Solicitors Code of Conduct can be found at www.sra.org.uk Hägen Wolf Limited is registered at Companies House No. 10830060. Registered Office: One Park Row, Leeds, LS1 5AB. We use the word 'partner' to refer to a shareowner or director of the company, or an employee or consultant who is a lawyer with equivalent standing and qualifications.

Site by: elate global

Contact us

Give us a call on 0330 320 1440 or send us an email at hello@hagenwolf.co.uk or fill in the boxes below and pop over a quick message and a member of the team will get back to you as soon as they're free.